Resolving Baudrillard’s Paradox: A Study in Southern Italian Philosophy

by Dr. Oleg Maltsev

When we set out to study the philosophy of Southern Italy as a cohesive system, we understood that the task would not be an easy one. Philosophy is a multifaceted and multifarious discipline, which means that, for a thorough investigation, it is first necessary to outline all its aspects and pose the right questions. As is often noted, a well-constructed question represents half the success, yet finding answers to these questions remains crucial. Remarkably, it was precisely the endeavor to explore the philosophy of Southern Italy that led us to resolve Baudrillard’s paradox. This study was conducted during the 2019 expedition to Calabria and thoroughly documented in the monograph Philosophy of Southern Italy (Maltsev, 2020).

The central thesis of Baudrillard’s paradox is the concept of the “copy without an original,” or simulacrum, a term that has gained increasing relevance. Simulacrum, in fact, forms the foundation of our civilization, as humanity constantly operates within this paradox. People exist within a simulated world that simultaneously constitutes their reality as hyperreality and is fundamentally insubstantial. Jean Baudrillard successfully identified and described this phenomenon but was unable to explain its origins or mechanisms. In our context, the paradox manifests as follows: what is conventionally regarded as philosophy in the scientific discourse of the 21st century is, unfortunately, not philosophy in its entirety but merely a component of it.

This issue became evident during our study of philosophy of Southern Italy, particularly during the Calabrian expedition. It was during this expedition that I developed a particular model, which became the starting point for the study and ultimately led to the resolution of Baudrillard’s paradox. The resolution is detailed in my book Maestro. The Last Prophet of Europe (Maltsev, 2021). In this article, I will discuss the research process, present the methodology that was developed, and share insights that were omitted from the book.

The Reason Behind My Study of Baudrillard’s Paradox

Initially, when we began our expeditionary work in Southern Italy, the goal was not to resolve any of the paradoxes described by Baudrillard. The first and foremost question we faced was how to determine that we were studying and engaging directly with philosophy as a complete system. In other words, where is the proof that we are dealing not with fragments of philosophy, but with a complete work? What parameters define that the subject of our study is fully described? There must be something that verifies and repeatedly demonstrates the completeness of the work from different angles, so that the researcher is confident in its integrity and the quality of the work done. Often, a scholar in such cases asks, “What will I use?”—for example, what tool or heuristic model.

Through many years of research in Southern Italy and the study of organized crime, it has become evident that even within academic circles, confusion often arises between criminal tradition and criminality. Here is a question to consider: which came first, crime or law enforcement system? Crime creates the need, and law enforcement is the response. Since crime is seen as a socially unacceptable phenomenon, the idea that “crime gave birth to law enforcement” is not a widely embraced paradigm. This reversal of cause and effect often leads to misunderstanding. Researchers should strive to eliminate such societal biases, keeping in mind that phenomena deemed unacceptable in our time may have been perfectly normal and accepted in the past centuries. For instance, European knights, who were responsible for numerous acts of violence, are now honored as historical heroes.

Most of the phenomena we encounter in the 21st century have roots that stretch back through the centuries. The criminal traditions of Southern Italy didn’t emerge today or even a decade ago; they originated three thousand years ago, evolving and transforming into what they are now. When conducting research, we cannot apply modern standards of decency, social acceptability, or morality to such ancient phenomena, as the criteria during their formative stages may have been entirely different.

Why did we choose Southern Italy’s philosophy as our research focus?

It is because there is no philosophy more effective for life than that of Southern Italy. What justifies this statement? My friend and colleague, Italian professor Antonio Nicaso, a leading criminologist and international expert on organized crime, particularly the Calabrian criminal organization ‘Ndrangheta, was once asked whether it is possible to defeat the ‘Ndrangheta. His response was brief and definitive: “There is no way.” At the same time, combating such organizations costs huge funds every year. According to him, the influence of ‘Ndrangheta is now global, reaching even the highest levels of government. “If ‘Ndrangheta were removed, the entire European economy would collapse,” he concluded (Nicaso, 2019). What is the reason behind the effectiveness of this criminal organization? It lies in its philosophical and psychological approach to life, which has allowed it to remain the most powerful organization to this day. Researching such structures, in turn, reveals what is ineffective in our own systems. Why can’t the global community deal with the ‘Ndrangheta? Because it is less effective than the ‘Ndrangheta.

Another “trap” that researchers fall into is equating philosophical works with philosophy itself. Kant’s books and Kantian philosophy are two different things. One can come across a book, but that doesn’t necessarily describe the philosophy. You might read all of Kant’s works and still not grasp his philosophy. When it comes to the philosophy of criminal traditions, we face the absence of books—there are no textbooks on the philosophy of the Mafia, Camorra, or ‘Ndrangheta. Therefore, in studying the philosophy of Southern Italy, the first question that had to be addressed was the methodology of researching philosophy.

Ahead of our upcoming expedition to Italy, we developed a research concept for philosophy that revealed all world philosophies are structured in the same way. The reason we can’t answer certain questions is simply because we lack a full understanding of them. The methodology we developed allowed us to describe not only the philosophy of the Camorra, the Mafia, and the ‘Ndrangheta, but also the overarching philosophy of Southern Italy. Next, we propose to outline the research program, i.e., the questions and elements of philosophy that needed to be identified and described (more details can be found in my monograph Philosophy of Southern Italy, but here I will only list them):

- Amalgam.

- Wisdom in sayings.

- Riddles and proverbs.

- Codes and behavioral rules.

- Rituals.

- Perspectives of masters.

- Views on men and women.

- Philosophical hierarchy.

- The role of weapons, objects, and attributes.

- The role of non-human entities (e.g., figures from European mysticism).

- The role of fate in philosophy.

- Language, symbols, and the secret language.

Once the main analysis of philosophy has been completed, covering all the previously examined aspects, it is essential not to neglect the mode of production. The mode of production is one of philosophy’s most vital elements because it satisfies the individual’s need for survival and well-being. Without it, the entire philosophy lacks meaning. It is unlikely that anyone would truly desire to follow a philosophy that leads to poverty. It is important to recognize that life-related attributes, such as wealth creation and success formulas, presuppose that philosophy requires a base. The realm of social production, circulation, and reproduction thus serves as the “soil” in which philosophy grows. For example, medieval philosophy is tied to the world of knights, while modern philosophy is rooted in consumer society. A philosophy without such a foundation is inconceivable. The conclusion is that the concept of soil is indispensable in philosophy, whether in daily belief systems or specific philosophical systems developed by individuals. This concept, however, is largely overlooked by modern science, which leads us to an important question: What type of soil will nourish a philosophy?

“Environment – Construction of Philosophy – Soil” Model

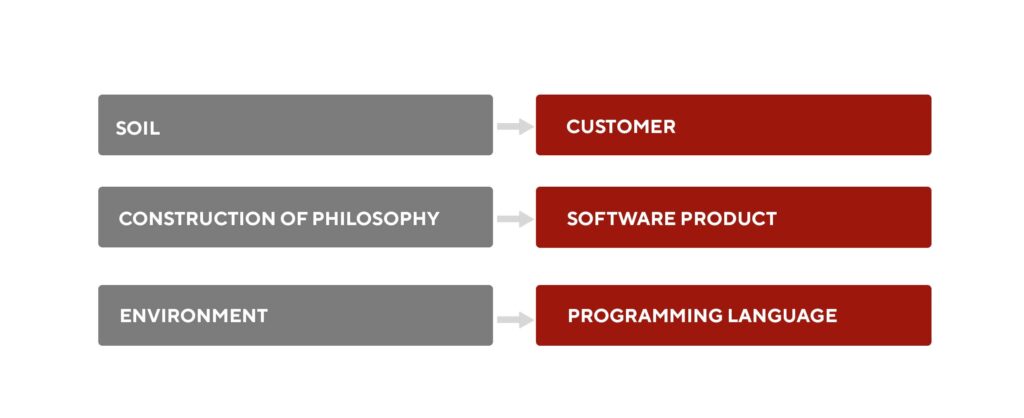

In the course of studying philosophy as a system, three key questions emerged:

• Who is the intended audience for this philosophy?

• What does the construction of philosophy entail?

• What was used to create this construction?

In simpler terms, this can be described as:

• A system (for example, a programming language),

• The resulting software product,

• And the user (consumer) who uses the program.

(I believe this example will be most understandable to the modern person.)

In scientific terms, this system would be represented as:

• The user is the “soil” onto which philosophical ideas are sown (a variable magnitude).

• The software product is the “construction of philosophy” itself, which is unique in nature, as it is not a constant value—it changes (it can be modified as needed based on the condition of the soil).

• The programming language is the “environment”.

The soil is one of the most fundamental elements of philosophy that exists. What kind of soil will philosophy fall on? If we consider the example from the legend of Favignana Island, it speaks of the Tree of Knowledge, where seeds falling on fertile soil will bear fruit, while those that fall on infertile soil will not (Karuna, 2019). We must examine what “soil” means from a research perspective. The concept of soil encompasses people and their psychological state, mindset, abilities to comprehend, and a whole systemic complex that describes the soil. To do this, we must study the space and the people within it to understand what kind of soil exists there and whether this philosophy will bear fruit on that soil. Note that part of the philosophy involves cryptography (secret language), which likely characterizes a level in the organizational structure, as cryptography is primarily needed by leaders to give secret orders (Trumper et al., 2014). All these aspects of philosophy are interconnected and converge on figures of European mysticism. At the same time, each organization has its own philosophy, but they all fall under the unified philosophy of Southern Italy.

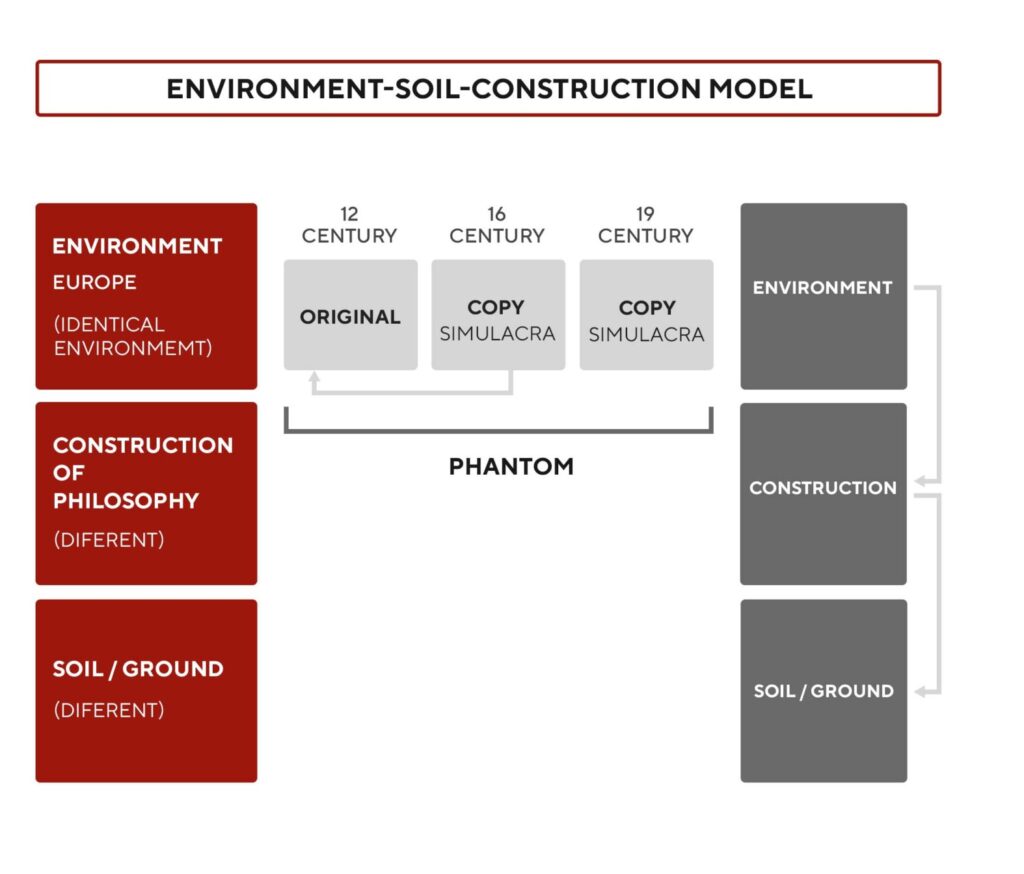

Now, let’s consider a heuristic model for resolving the Baudrillard paradox. These are three main components: soil, environment, and construction of philosophy.

The environment functions as a programming language—a system understood only by its “developers.” It is the constructor of everything, containing an exhaustive array of data and knowledge. The construction and foundation of all philosophies will vary. The environment of Southern Italy, for example, is rooted in European mysticism. The construction and soil of each philosophy will differ. The soil, on which the seeds of philosophy fall, represents the people for whom this philosophy is intended. The philosophy’s construction is a mutable component, and it also creates the hierarchy. When the environment and soil interact, a certain construction arises. A specific set of soil that corresponds to the environment eventually gives rise to an intermediate, unstable construction, which also contains both constants and variables. Over time, the construction continuously transforms by incorporating missing elements from the environment, adjusting and correcting itself to align with the soil, in order to keep existing.

Thus, the construction, with its constants and variables, will continuously change because, above all, the soil will transform, which will require the construction to align with the soil and, for that, to use the environment. In this way, the construction is modified (restructured) to fit the soil. Overall, these three elements will either remain in balance with each other or strive for equilibrium during the moments of transformation.

In our research, the environment represents the entire system of philosophy of Southern Italian, while the construction can be the philosophy of the ‘Ndrangheta. In other words, the general philosophy of Southern Italy will differ from the philosophy of the ‘Ndrangheta because we are dealing with the general (Southern Italian regional philosophy) and specific elements (the philosophy of subcultures in the region—the philosophy of the Mafia, Camorra, and ‘Ndrangheta). Each of these organizations, the Mafia, Camorra, and ‘Ndrangheta, will have its own construction of philosophy, while maintaining the same systemic elements of Southern Italian philosophy (Ciconte et al., 2010).

The “environment—soil—construction” paradigm applies universally to all philosophies, as without it, they could not have endured until today. If a phenomenon emerged at some point and continued to exist through the 21st century, it must possess these constructions, along with a shared environment that enables the construction to adapt according to the soil. This is especially evident in the psychology section, where we observe clear differences in the approaches of the three organizations (this is elaborated in the monograph). While there is a unified philosophy and common amalgam in Southern Italy, the philosophical construction of each individual organization will differ from the others.

Thus, we come to an important conclusion:

If this system had not evolved in response to the demands of the external environment, if it had not been subject to adjustments, it would not have survived to the present day.

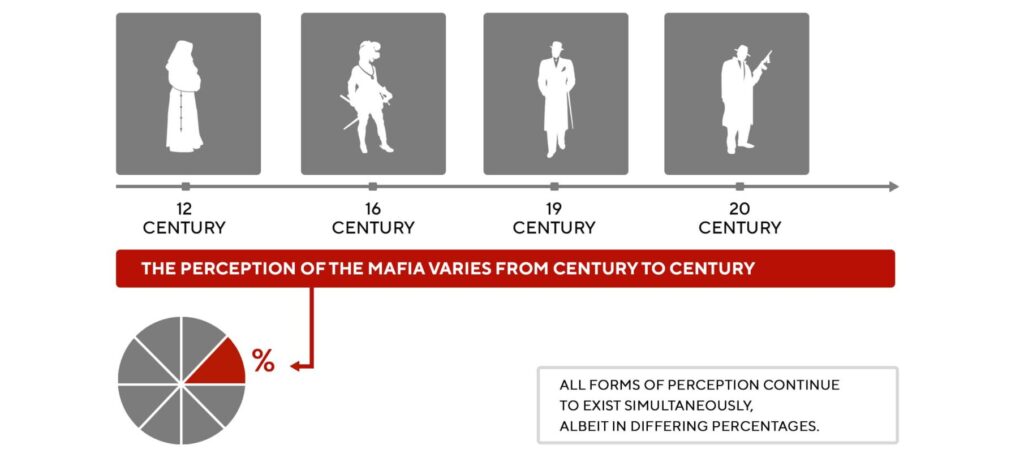

However, an important point to address is accounting for historical periods by applying the “soil-environment-construction” model to the timeline, which covers the various historical stages the phenomenon has experienced. It’s crucial to situate a given historical group or social force within its own philosophy, examining how this philosophy relates to both its contemporary context and its historical development. The structure of the Mafia in the 12th century differs from that of the 16th, 19th, and modern times. However, both the general public and most scholars not only fail to recognize this model but also overlook the historical aspect. As a result, a phantom is created—one constructed from fragmented pieces, misunderstandings, and fabrications, which over time merge into a unified illusion. Nobody truly knows how the Mafia is actually structured. Different elements from various historical periods come together, creating a simulacrum, a copy without an original, as Jean Baudrillard would say (Baudrillard, 1994).

For example, one might study the “Mafia” of the 16th century without grasping the overall structure of the phenomenon (it should be noted that the term “Mafia” is used here in a conventional sense, as it did not have the same meaning in the 12th or 16th centuries). Another scholar might investigate only the “Mafia” of the 19th century, without considering the earlier periods. Each would develop a snapshot of “the Mafia” from which they could reverse-engineer a model or blueprint. Yet, this would omit the historical context of both its past and present. In essence, although both instances might be referred to as the Mafia, the two versions of the Mafia described would vary greatly from one another. Baudrillard’s paradox is rooted in the absence of awareness about the historical and socially situated construction of an entity, and the ignorance of what its original form truly was. Over time, different synchronic interpretations of the entity are reconstructed, creating a fragmented understanding.

Due to this reification, people posit an organizing form other than its actual origin, turn this into a blueprint which can be replicated, and different “phantoms” emerge—each of which is a simulacrum, a copy without an original in reality. If one takes into consideration “soil”, “construction” and “environment” simultaneously, one will not fall into this trap and will be capable of accurately assessing whether one is dealing with the original, a copy or modification, or a “phantom” simulacrum.

The same is true for philosophy—everyone only knows a part of it, the “phantom.” To understand it fully, all fragments must be pieced together, but no one does this. As a result, two systems exist: the “phantom” one and the actual one. The distinguishing feature of the actual system of philosophy of Southern Italy is that it is nearly impossible to enter—it has a “guardian,” much like in the legend of Favignana Island, where lions guard the entrance to the garden, preventing anyone from entering without permission. Once inside, there is no way back.

To begin the study of any philosophy, it’s essential to first identify these three components: environment, construction of philosophy, soil. Next, these components and their transformations over time need to be examined. In other words, we must first break the phantom into its phantom parts, and only after verifying these components with heuristic models and mathematical measurements, can we conclude that the philosophy has been thoroughly studied.

Because no one follows this approach, we find ourselves dealing with individuals who discuss phantom representations of philosophy without any real grasp of the subject. This problem isn’t limited to philosophy; it permeates psychology, sociology, and all humanities disciplines. Baudrillard’s paradox represents the central “illness” of the humanities, as opposed to the exact sciences like mathematics and physics, where formulas, figures, and calculations can be tested and verified.

Why are the humanities considered the most complex sciences? It’s because determining the truth is incredibly difficult in these fields. Mathematics follows strict mathematical laws, which a scientist cannot violate. The humanities, on the other hand, are full of abstraction, leading to numerous interpretations, misconceptions, and paradoxes. If we examine any school of psychology, we find that the soil is unknown, the environment is unclear, and the construction is shaped by the current formation of the field, as seen through the eyes of the person presenting it to you.

What Came First?

Returning to the original question of which came first — crime or the law enforcement system? Note that we are dealing with a phantom counter-construction that has the ability to transform into specific systems. This is how the law enforcement system emerged as an alternative. Essentially, the world is structured differently than we imagine, and the derived heuristic model explains why this is the case. It provides an understanding of why phantoms — copies without originals — arise, and why counter-systems, also of a phantom nature, follow. A phantom can transform into counter-constructions.

What is the difference between a counter-construction and a construction? The counter-construction has neither an environment nor a soil; it is a phantom of the construction, existing due to centuries of history and transforming, for example, into the police, into the “X” counter-system. This is how numerous counter-systems have emerged, created as opposites to existing systems. The phantom counter-system can materialize in different forms. And Baudrillard’s paradox only fully proves this construction. This is how the system works, and in order to understand philosophy, one must not just comprehend the current construction, but follow the entire process outlined above.

Essentially, in this article, I have briefly presented a model for studying philosophy, psychology, fencing, criminal traditions, and many other phenomena.

Thus, as a result of the conducted research, we were able to resolve Baudrillard’s paradox using the example of the philosophy of Southern Italy. This model is applicable to various fields of study, as it enables one to break down the phantom into its components and reach the essence, the “original.”

People often substitute impressions for knowledge, mistakenly believing that these are the same. Many professors, in fact, consider knowledge to be a form of delusion. This is because there is no clear answer to the question: how do I know if I know everything about a subject or not? The distinguished academic G. S. Popov once said, “Nothing changes in the world; everything takes some form of absurdity.” In most cases, when we encounter something, we are dealing with a phantom, and we need to seek the original, the primary source. Baudrillard’s paradox vividly demonstrates that when the content is unknown, the title holds no real meaning—it always misleads us.

The one who has solved Baudrillard’s paradox can quickly study everything necessary and describe this system at any stage of its existence.

References

Baudrillard, J. (1994). Simulacra and simulation. University of Michigan Press

Ciconte, E., Macrì, V. & Forgione, F. (2010). Osso, Mastrosso, Carcagnosso. Immagini, miti e misteri della ‘ndrangheta [Osso, Mastrosso, Carcagnosso. Images, Myths, and Mysteries of the ‘Ndrangheta]. Rubbettino

Maltsev, O. (2020). Philosophy of Southern Italy. Serednyak T.K.

Maltsev, O. (2021). Maestro. The Last Prophet of Europe. Publishing House “Patriot”

Nicaso, A. (2019, October). Lectures. [Unpublished lecture, Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, Odesa branch, Odesa].

Trumper, J., Gratteri, N., Nicaso, A., & Maddalon, M. (2014). Male Lingue: Vecchi e nuovi codici delle mafia [Evil Languages: Old and New Mafia Codes.]. Pellegrini.

Karuna, D. (2019). Pyat let mechtal popast na ostrov Favinyana… i vot ya zdes! [Been dreaming of getting to Favignana Island for five years…and here I am!] Expedition. https://expedition-journal.de/2019/12/03/ya-pyat-let-slyshu-ot-kapitana-o-favinyane-i-vot-ya-na-nej/

Discover more from BAUDRILLARD NOW

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.