On the Entanglement of Contemporary Future Imaginaries: Conceptualizing the Matrix and the Brain-Machine Interface from Baudrillard and Gibson to Musk

by Dr. Jiré Emine Gözen

(Tweet of Elon Musk on the 21st of February 2021 on Twitter)

This article examines the historical entanglement of Jean Baudrillard’s media theory concepts with cyberpunk science fiction literature in the late 1980s. It argues that one significant outcome of this entanglement was the development of specific future imaginaries whose impact remains highly influential to this day. The article posits that the foundation of this intertwining was a rupture within science fiction literature itself, a rupture closely tied to the rise of postmodernist thought and, particularly, to Baudrillard’s reflections. This shift gave rise to cyberpunk literature, in which technology and humanity are no longer depicted as separate entities. Instead, a unity of man and technology was postulated, in which the further development of man was henceforth conceived. Authors such as William Gibson played a pivotal role in this transformation, with his works reaching well beyond the traditional readership of science fiction. Using the terms and concepts of interface and the Matrix taken up and further extrapolated by Gibson, their further use in the context of the invasive future technology developed by Elon Musk’s company Neuralink is used as an example to show that and how they still have an effect today. This article serves as an extension and further exploration of the earlier work, “Chambers of the Past and Future: The Simulated Worlds of Baudrillard, Cyberpunk, and the Metaverse,” published in this journal in April 2023.

Introduction

The concept of imaginaries plays a central role in the discourse surrounding society’s conceptions of the technologies of the future. The term refers to something “invented or not real, something projected into the future, imagined beyond itself” (James, 2019, p. 37). It encompasses visions that often extend beyond current realities to imagine the future. Particularly relevant are “sociotechnical imaginaries,” described by Jasanoff (2015, p. 4) as “collectively held, institutionally stabilized, and publicly performed visions of desirable futures, animated by shared understandings of forms of social life and social order attainable through, and supportive of, advances in science and technology.” These collective visions are not simply abstract ideas but institutionally embedded and publicly enacted images of desirable futures, intended to be realized through scientific and technological progress. While “sociotechnical imaginaries” are “not mainly defined by discourse but are often associated with active exercises of state power and the management of political dissent” (Harvard Kennedy School, n.d.), “future imaginaries” are understood as images, visions, and scenarios of the future conceived and propagated by individuals or groups (Kleske, 2019). When these visions become so deeply ingrained in society that they go unquestioned and uncritically guide behavior, they transform into “future imaginaries.” In this way, visions of the future become pivotal elements of societal reality, profoundly shaping both actions and thought. The concepts of “sociotechnical imaginaries” and “future imaginaries” underscore the intricate relationship between technological development and societal expectations and visions of the future. In what follows, I will use the term future imaginaries because it is more appropriate to the context of the argument presented here, as it has a somewhat broader scope. However, there is considerable overlap between the two concepts, so in many places the term sociotechnical imaginaries could also be used.

Engaging with the discourse on the development of future technologies today makes it nearly impossible to avoid the media-saturated projects and grand visions of Elon Musk. The wealth Musk accumulated through his founding role in PayPal has been funneled into ventures such as SpaceX, Tesla, Inc. (formerly Tesla Motors until 2017), OpenAI, and Neuralink. The technological ambitions of Musk, a South African-born, Canadian-American entrepreneur, often evoke comparisons to science fiction. SpaceX, for example, was founded with the goal of developing the technologies necessary for the colonization of Mars. In pursuit of this objective, the company has become the leading commercial provider of orbital rocket launches. Musk remains steadfast in his commitment to sending crewed missions to Mars by 2030 and fully colonizing the planet by 2050 (Exodus, 2020). However, it is essential to critically examine the underlying colonial dynamics that shape this vision—not only in an epistemological sense but also in the concrete plans for human dominion over new territories, where societal and governance structures reflect power imbalances and labor conditions reminiscent of the colonial era. Tesla, in addition to producing electric vehicles, also develops photovoltaic systems and energy storage solutions, positioning itself as a provider of sustainable alternatives for a future defined by resource scarcity. OpenAI, founded in 2015 as a nonprofit organization, was launched with the goal of advancing artificial intelligence and ensuring its benefits for society and launched the widespread Chatbot ChatGPT in 2022. Musk withdrew from the project in 2019 due to conflicts of interest (Hyperdrive, 2019).

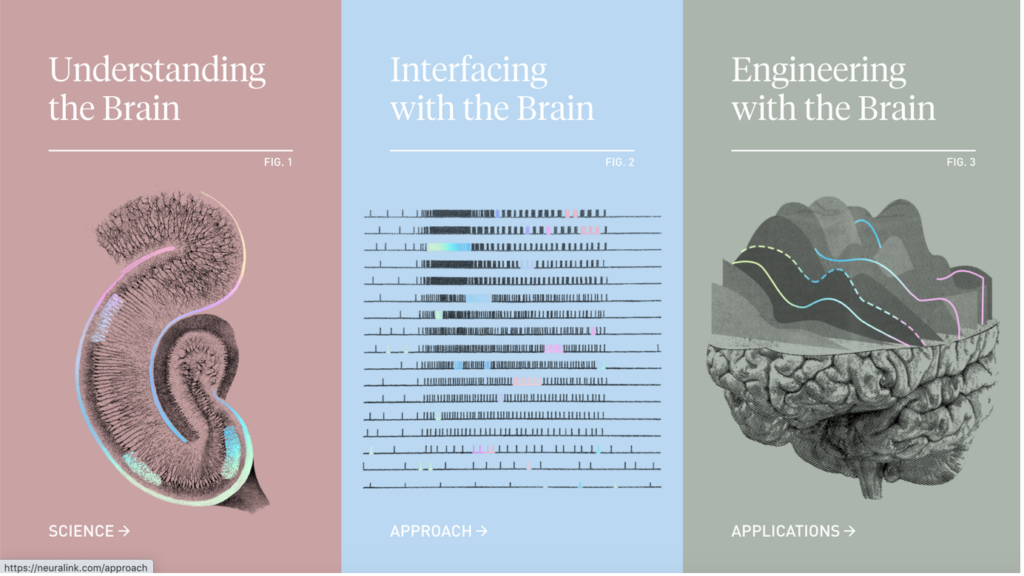

Neuralink, founded in 2016, is a neurotechnology company with the ambition of connecting the human brain directly to computers via an interface (LA Times, 2017). Initially, this invasive neuroprosthesis is intended to treat disorders of the brain and central nervous system, but its long-term goal is to enhance human capabilities, enabling humans to keep pace with the rapid development of artificial intelligence (Ars Technica, 2017). In 2024, the first successful chip implantations in partially paralyzed individuals were performed. Despite critical media coverage and some setbacks, these procedures can still be considered a preliminary success within a limited scope (Jewett, 2024). Given that Neuralink’s groundbreaking technology is frequently described with terms like „interface“ and „Matrix“, important questions arise about the imaginaries associated with these concepts. What are their historical contexts? Under what circumstances did these terms emerge and become established? What meanings have they acquired, and how were they popularized? These questions are crucial to understanding the broader cultural and philosophical implications of the technology Musk seeks to develop and how this is perceived and understood by a broader public.

(Screenshot from Neuralink.com, 13.05.2022)

The thesis of this paper is that the terms and concepts used to describe and discuss Neuralink’s invasive technology stem from an interweaving of science and fiction—specifically, the fusion of Jean Baudrillard’s media theory and cyberpunk science fiction. From this convergence, distinct future imaginaries emerged, whose impact on contemporary thought is profound and far-reaching. This paper argues that the foundation for this interweaving was a rupture within science fiction literature in the 1980s, from which the cyberpunk genre was born. This rupture was characterized by a shift in how cyberpunk authors depicted technology and humanity—not as separate entities, but as an integrated unit through which the future evolution of humankind would be imagined.

A pivotal figure in this shift was William Gibson, who, during the 1980s, achieved widespread popularity beyond the traditional confines of science fiction readership. This recognition was partly due to theorists like Frederic Jameson, Douglas Kellner, Rainer Winter, and John Fiske, who identified Gibson’s narratives as engaging with and extending certain media-theoretical discourses. These theorists frequently referenced Gibson and the cyberpunk movement in their own work, using Gibson’s fiction not only to illustrate theoretical concepts but also to explore their wider implications. In doing so, they not only reinforced their own theoretical positions but also introduced Gibson and cyberpunk into academic discourse, significantly contributing to Gibson’s growing popularity and the increasing recognition of his extrapolations of the future. His imaginaries of the future began to permeate broader cultural discourse, a rare feat for science fiction, which had long been dismissed as pulp literature (Atterbery, 2003). By the 1980s, these imaginaries were informing societal discourse about the future trajectory of digital technologies, shaping visions of technological evolution both in the near and more distant future—futures that still felt personally relevant. Concepts like the Matrix, Cyberspace, and the interface thus became part of a collective understanding of what the future might hold and thus future imaginaries (Gözen, 2012).

This paper is organized into three sections. First, I will demonstrate, through specific examples, that the terms „interface“ and „Matrix“ are central to discussions of Neuralink’s technological developments. To provide a framework for this, I will trace the genesis of these terms, showing that their application to Neuralink can be traced back to William Gibson, who in turn drew heavily on Jean Baudrillard’s ideas (a connection that will be explored further in the third section). In the second section, I will argue that Gibson’s use of these terms and concepts marks a fundamental break with the traditions of science fiction. To contextualize this shift, I will examine the history of science fiction and the values and ideas it has traditionally conveyed. Finally, in the third section, I will explore how the interweaving of media theory and cyberpunk came about, ultimately demonstrating that the conceptual framework used in contemporary discussions surrounding Neuralink owes much to this fusion of science and popular culture.

Interface and Matrix: Neuralink’s Technological Dream of Bridging Minds and Machines and Gibson’s Cyberpunk Legacy

The company Neuralink, founded in 2016, has set the ambitious goal of developing the first neural implant capable of establishing a direct connection between the human brain and computers or mobile devices, allowing them to be controlled purely through thought. While the initial focus of this technology is on compensating for neurological damage caused by illness or injury, the long-term vision is far more expansive: creating a system through which humans can connect not only with their devices but also directly with one another. In Musk’s vision, this could lead to a future where humans no longer need spoken or written language for communication. Instead, thoughts could be transmitted directly through a network linked to Neuralink’s technology, allowing them to be received and understood by another person’s brain. The feasibility of such a vision in the near future is the subject of significant debate, with many critics questioning Musk’s ideas and, in some cases, dismissing them as unrealistic and unethical (Hart, 2024). Nonetheless, Neuralink’s projects have generated widespread media attention, and their impact on current discussions of what might be technologically possible in the future is substantial. This influence is likely bolstered by the fact that Musk’s ideas do not emerge in isolation but are articulated within existing conceptual frameworks and discourses, building on them in meaningful ways.

The idea of a brain-computer interface is, in fact, not a novel concept. As early as the 1940s, Norbert Wiener, the so called father of cybernetics, explored the analogies between the human brain and computers. Since then, the possibility of direct communication between brain and machine has been a recurring theme in both scientific research and speculative fiction. Recent advances in technology miniaturization, along with new breakthroughs in neuroscience, have led to some early achievements in this field (Science Media Center, 2020). For example, in 2017, a team of brain and computer scientists led by Daniela Rus at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) developed a feedback system that enables human brain activity to be transmitted to robots (Technology Review, 2017). In 2019, French researchers led by Alim Louis Benabid reported in „The Lancet Neurology“ on a quadriplegic patient with two wireless devices implanted in his brain, recording his brain activity (Benabid et al., 2019). Neuralink now refers to its work as “Interfacing with the Brain,” announcing: “Neuralink is building a fully integrated brain machine interface (BMI) system. […] BMIs are technologies that enable a computer or other digital device to communicate directly with the brain” (Neuralink, 2020). For the purposes of this article, the choice of the term „brain-machine interface“ to describe an invasive neuroprosthesis is particularly noteworthy.

The term “brain-machine interface” first appeared in scientific literature in 1973, in a paper by Belgian computer scientist Jacques J. Vidal at the University of California, Los Angeles (Nicolas-Alonso, 2017). While research in this area remained relatively quiet in the scientific community until the late 1980s, cyberpunk science fiction authors, particularly William Gibson, adopted the concept and expanded on it in their fictional works. In his 1982 short story „Burning Chrome“, Gibson envisions a world in which humans use a brain-machine interface to directly access computer-generated data landscapes. To describe this future vision, Gibson employed the term „interface“ for the first time in relation to immersing oneself in a computer-generated virtual space. Notably, he adapted the term to describe both an activity and a state: „Trying to remind myself that this place and the gulfs beyond are only representations, that we aren’t ‘in’ Chrome’s computer, but interfaced with it, while the matrix simulator in Bobby’s loft generates this illusion . . .“ (Gibson, 2003, p. 264).

This evolution of the term interface, as Gibson used it, marks its transformation from a technical concept into a metaphor for human interaction with virtual environments, a shift that profoundly influences how we conceptualize technologies like Neuralink today. In a 2014 study that provides a historical and cultural-theoretical analysis of the term, Brandon Hookway described the interface in relation to machines „as a relation with technology rather than as a technology in itself“ (Hookway, 2014, p. ix). He concludes that the interface should be understood as a „continual stream of sensory and cognitive data ranging from visual cues and instrument readings to kinesthetic and vestibular senses of balance and motion,“ and thus as „a productive form of illusion, an illusory knowledge“ (Hookway, 2014, p. 74). Hookway’s vivid description of the interface as a flow of sensory and cognitive data that creates an illusion strongly echoes Gibson’s literary depiction of the virtual space created by a human-machine interface, first imagined in „Burning Chrome“ and further developed in his 1984 novel „Neuromancer“: ‚THE MATRIX […] A consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators, in every nation, by children being taught mathematical concepts… A graphic representation of data abstracted from the banks of every computer in the human system. Unthinkable complexity. Lines of light ranged in the nonspace of the mind, clusters and constellations of data. Like city lights, receding . . .‘” (Gibson, 2003, p. 108).

In both „Burning Chrome“ and „Neuromancer“, the interface is directly linked to the Matrix alas the cyberspace, as it is the medium that grants access to the virtual world. It is important to note that the term cyberspace is a neologism—an entirely new word. Gibson has stated that the idea for the term came to him in 1981 when he was searching for a word to describe the “non-graphical space” of the future, where humans and computers would exchange information. Initially, he used the term „infospace,” but after scribbling on a notepad, he coined the term „cyberspace“. The term Matrix is used analogously to cyberspace. Both cyberspace and the Matrix refer to the virtual space itself as well as its structural framework. Gibson derived the term Matrix from both the Latin word for „womb” and the mathematical concept of a matrix. Gibson also introduced Matrix as a place where the mind resides when connected to machines, thus expanding its meaning.

Whether Matrix or cyberspace, both terms convey the idea of a virtual reality that has yet to be technically realized. They articulate a vision of virtual reality that completely envelops the human experience, rather than conceptualizing humans as autonomous entities standing apart from the virtual world. The immense success of Gibson’s novel „Neuromancer“ led to the neologism cyberspace and the concept of the Matrix shaping the imagination of entire generations regarding the future of virtual data spaces and computer networks. While cyberspace has since entered the dictionary, Gibson’s concept of the Matrix gained further prominence through the Matrix film series by the Wachowski siblings, beginning in the late 1990s. Thus, it is unsurprising that Gibson’s visions are still regarded as almost prophetic today (William Gibson: The man who saw tomorrow, 2014).

The concept of an interface as the crucial link between humans and machines is central to Gibson’s vision of cyberspace and the Matrix; they are conceptually intertwined and mutually dependent. Without the interface facilitating the connection between brain and computer, it would be impossible for humans to link their consciousness to the virtual data space, rendering the Matrix a realm beyond human perception. It is therefore both logical and significant that Neuralink employs the term interface to describe the human-machine connection they aim to create through their neuroprosthesis, designed to directly network humans with their technological devices.

(Screenshot of Tasmanian.com, 13.05.2022 and of a Tweet of Elon Musk on 20.07.2020)

It is also notable that in 2020, ahead of a presentation on Neuralink’s latest developments, Elon Musk referred to „the matrix in the matrix“ (Tesmanian, 2020) to explain how the presentation would display real-time neuron activity in the brain via the interface. The associative link between the brain-machine interface and the Matrix, which underpins Neuralink’s broader ambitions, is strikingly clear here: Musk invokes specific, pre-existing discursive images and ideas to describe and make comprehensible the potential impact of this emerging technology. Similarly, Gibson’s terms and concepts are frequently referenced in media discussions surrounding Neuralink. Within the tech community, which engages through platforms like Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter (now X), questions such as „Is Elon Musk creating the Matrix?“ (SiddharthVlogs, 2020) and „How Close Is Elon Musk’s Neuralink to Ushering Us into the Matrix?“ are posed. The MIT Technology Review, in its coverage of Neuralink, references „Pigs in the matrix“ (Technology Review, 2020). Major publications like The New York Times (Metz, 2019), The Irish Times (Moran, 2019), and industry journals such as Robotic Biz also intertwine their discussions of Neuralink and Musk with Gibson’s dystopian visions. For instance, the introduction to an article titled „Neuralink – A Step Closer to Human-Machine Symbiosis“ reads: „The dystopian world of William Gibson’s Neuromancer and the birth of the cyberpunk genre created visions of a reality where people were able to connect with machines, acquiring unprecedented abilities. With their brains plugged into their cars, they were better drivers, and when their minds entered cyberspace, they became better hackers. How much of that fiction is possible today?“ (Robotic Biz, 2020

It becomes clear that the brain-machine interface represents far more than a mere technical connection between humans and computers. It embodies broader future imaginaries that shape societal visions and expectations of the future. These future imaginaries are deeply rooted in cyberpunk literature, and for various reasons, have permeated and continue to influence contemporary technological discourse. The following section will explore the historical contexts that explain the unique influence of cyberpunk science fiction in shaping today’s technological narratives, particularly those surrounding developments like Neuralink.

Their critique was particularly aimed at traditional science fiction’s adherence to a humanistic thought tradition, which assumed the existence of an inherent, timeless human nature. This belief positioned the human mind and reason as immutable constants, with media and technology always perceived as external forces, separate from the individual. For the cyberpunk authors, however, human thought and the psyche were not seen as unchangeable or inherently „pure“ states. They observed that technology was no longer „some bottled genie of remote Big Science boffins,” but rather, “pervasive, utterly intimate […] not outside us, but next to us“ (Sterling, 1988, p. xi) and already penetrating the deepest layers of human existence. For cyberpunk writers, the artistic task was to reflect on how technology was fundamentally transforming both individuals and society. The foundation of the cyberpunk movement’s ideas lay in the rise of a new „technical culture,“ (Sterling, 1988, p. xiv). in which emerging computer, media, biological, and medical technologies increasingly permeated everyday life. As Bruce Sterling famously noted, „technology […] has slipped control and reached street level“ (Sterling, 1988, p. xi). The cyberpunk writers believed that contemporary science fiction needed to engage with this shift, rather than resist it. Accordingly, they sought new literary forms that could reflect and explore the unsettling technological developments of their present. At the heart of cyberpunk literature lies the theme of radical transformation and disruption of what it means to be human, driven by media and technology. Cyberpunk narratives fundamentally deconstruct the unity of the mind, the immanence of the soul, and the essence of humanity itself.

In 1983, Bruce Sterling, the de facto spokesperson for the cyberpunk movement, launched the do-it-yourself fanzine „Cheap Truth“, which was published quarterly until 1986. Modeled after the aesthetics of 1970s punk fanzines, „Cheap Truth“ was typewritten and arranged in a collage-like style with images and newspaper clippings, then distributed as photocopies. From the third issue onward, it was also available on a bulletin board system (BBS). The cyberpunk writers believed that the content, themes, and form of traditional science fiction had long since become outdated, and they sought to fundamentally revitalize the genre. Their goal was to restore science fiction’s potential to engage with and reflect contemporary societal trends. In doing so, they aimed to bring science fiction back to the forefront of both entertaining and subversive popular culture. The cyberpunk writers expressed their critique of humanistic science fiction through polemics against figures like Isaac Asimov and Mary Shelley, whom they viewed as representing traditional, if not reactionary, backward-looking science fiction. A typical complaint was: „Why aren’t kids lined up eight deep for the latest issue of ISAAC ASIMOV’S? Why isn’t ANALOG doled out from locked crates by frowning members of the PTA? Because they are DULL. Worse than dull; they’re reactionary, clinging to literary-culture values while a cybernetic tsunami converts our times into a post-industrial Information Age“ (Cheap Truth, 1984). The literary values and traditions under attack are clarified further in other statements, such as: „[Humanist Science Fiction] promotes the romantic dictum that there are Some Things Man Was Not Meant to Know. There are no mere physical mechanisms for this higher moral law – its workings transcend mortal understanding; it is something akin to divine will. Hubris must meet nemesis; this is simply the nature of our universe“. (Sterling, 1991).

According to Sterling, the scientific and technological advances of recent decades had allowed humanity to acquire much of the “forbidden knowledge” that humanistic science fiction had long warned against. The application of this knowledge had, in many cases, demonstrated that humans act with little regard for the ethical and moral imperatives espoused by humanism: „As a culture, we love to play with fire, just for the sake of its allure; and if there happens to be money in it, there are no holds barred. Jumpstarting Mary Shelley’s corpses is the least of our problems; something much along that line happens in intensive-care wards every day“ (Sterling, 1991). In their writings for „Cheap Truth“, the cyberpunk authors argued that new, invasive technologies had initiated a paradigm shift, one that traditional science fiction had failed to foresee. They contended that the humanistic worldview had become so ingrained in the genre as an implicit myth that science fiction itself had fallen prey to outdated concepts. The original purpose of science fiction—enlightening its audience, offering essential scientific knowledge, and challenging outdated prejudices and superstitions—had, in their view, been abandoned. The references to figures like Asimov and Shelley should therefore be understood as historical framing devices, through which the entire tradition of science fiction, which the cyberpunk writers sought to critique, can be traced. This historical lineage will be examined in the following section.

From Mary Shelley to Asimov: Historical Antecedents and Conditions for Cyberpunk Writers’ Break with Traditional science fiction

Science fiction emerged as a distinct literary phenomenon under the unique conditions of the Industrial Revolution and the proliferation of the printing press in the 19th century. Mary Shelley’s „Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus“ (1818) is widely regarded as one of the first texts to introduce foundational motifs that have since come to define the genre (Slusser, 1992, p. 46). The novel is considered a seminal work, establishing a continuity from which the science fiction genre later evolved. Frankenstein reflects an era when technological advancements were profoundly reshaping both the natural world and human agency. Published during a period when innovations such as gas lighting, steam locomotives, and steamships were rapidly transforming human experience and everyday life, Shelley’s novel emerged within a context of seemingly boundless progress and limitless potential fueled by science and technology. Victor Frankenstein, the protagonist, embodies this belief in progress. His story, driven by a promethean ambition, is a familiar one: through his scientific endeavors, he succeeds in bringing life to inanimate matter, creating a human-like creature from organic materials. Shelley’s depiction of an overreaching scientist who, through technological means, creates a powerful entity that ultimately escapes his control remains a central theme in modern science fiction.

What distinguishes Frankenstein is that Shelley’s protagonist does not enter into a Faustian pact with a supernatural force like the devil—a notion rooted in an earlier belief system. Instead, the new driving force is science. Frankenstein’s ambitions bear fruit only after he abandons knowledge from the ‘pre-scientific‘ era in favor of contemporary scientific advancements, particularly in the field of electricity. In light of the technological developments of her time, Shelley’s narrative offers a reexamination of humanity’s place in a world increasingly shaped by the forces of the Industrial Revolution and modernity. At the heart of Frankenstein lie fundamental questions central to humanism: What does it mean to be human? Where does human essence reside? How can man ethically relate to one another?

Shelley’s Frankenstein also functions as a cautionary tale about the dangers of humanity’s unchecked pursuit of scientific knowledge. Seduced by the new possibilities that science and technology present, humans may be led to believe they are attaining god-like power, capable of creating life itself. However, as Shelley illustrates, such endeavors often result in consequences that are beyond human control and ultimately destructive. Implicitly, Shelley advocates for acknowledging a higher power that restores humanity to its rightful place in the universe, despite the dominance of modern ideologies. Literary scholar George Slusser refers to this notion as the „Frankenstein Barrier“, a concept rooted in Western thought and the belief that humans are created in the image of God. This idea has since become a foundational narrative within the science fiction tradition, especially in the Anglo-European context (Slusser, 1992, p. 46).

Following Frankenstein, classic science fiction authors built a genre-specific myth grounded in Western humanistic ideals, positioning humanity at the center of creation. As a result, beings created through the alliance of science and technology—such as robots—are often portrayed as existential threats. Philip K. Dick and Isaac Asimov, in particular, shaped the branch of science fiction focused on robots, imbuing their works with complex ethical and philosophical questions. Asimov’s „Three Laws of Robotics“ (first introduced in 1942) famously stated that a robot must never harm a human and must always obey human commands. These laws have had a lasting impact, influencing not only science fiction but also real-world robotics research and development, and continue to be referenced in contemporary debates on robot ethics. Although both Dick and Asimov critiqued the „Frankenstein Barrier“, their works ultimately reinforced the narrative that robots, in their quest to achieve equality with humans, pose a fundamental threat to the balance of power and must be destroyed. This theme continues in films such as „Terminator“, „Blade Runner“, „The Matrix“, and „I, Robot“. The consistent message is that technologically created beings are fundamentally distinct from humans and nature, and this separation must be preserved. As this belief system, rooted in Western thought, became more entrenched, the focus of science fiction increasingly shifted from philosophical inquiries to technological exploration (Information Philosophie, 2020).

Isaac Asimov emerged as a central figure in Hard Science Fiction (hard SF), a subgenre known for its meticulous attention to technical detail and its exploration of scientific possibilities. Many hard SF writers, including Asimov, had backgrounds in the sciences and incorporated cutting-edge research in fields like physics, mechanics, and space exploration into their stories. During the Cold War, as the arms race intensified, science fiction began to center more on space exploration, which became a symbol of the ideological struggle between the USSR and the USA. Space travel and futuristic designs shaped the cultural imagination of the future, and the mid-1960s television series „Star Trek“ reflected this fascination, resonating not only with the general public but also within scientific communities (Iglhaut, 2006, p. 256).

In the early 1980s, authors such as Jerry Pournelle, Robert A. Heinlein, and Larry Niven, alongside representatives from the space industry and the military, formed the „Citizens’ Advisory Council on National Space Policy“ to advise President Ronald Reagan on space exploration initiatives. Reflecting on this collaboration, Greg Bear noted, „Science fiction writers helped the rocket scientists elucidate their vision […] and Ronald Reagan, who read science fiction, said: ‘Why not?’“ (Cramer, 2003, p. 193). This highlights the intentional use of science fiction by the government to advance sociotechnical imaginaries that aligned with its political and technological agendas. It demonstrates that sociotechnical imaginaries were not simply cultural or creative constructs, but were actively and strategically leveraged by state actors to promote specific visions of the future. The deliberate integration of science fiction writers into the Citizens’ Advisory Council on National Space Policy and the advocacy for programs like the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) brought fictional future visions into the realm of political and public discourse. These imagined futures were not simply for entertainment—they were instrumental in presenting certain technological projects as inevitable, desirable, and achievable. The potential for crafting public acceptance of technological advancements deeply rooted in military and national security interests through carefully constructed sociotechnical imaginaries is particularly evident in this case.

Many members of the advisory committee supported the Strategic Defense Initiative, commonly known as „Star Wars“. The program was highly controversial, with critics warning that it could increase the risk of global nuclear conflict. Within the science fiction community, SDI and Reagan’s conservative policies met with resistance. Arthur C. Clarke, for example, vehemently opposed the SDI program, leading to a public confrontation with Heinlein. The growing politicization of hard SF ultimately led to deep divisions within the subgenre, as reactionary and militaristic ideas gained prominence. Many politically moderate or left-leaning writers distanced themselves from hard SF. Editor Kathryn Cramer observed, „the most generalized symptom of the reactions against the politicization of hard SF was a sense that good writers were turning away from the subgenre and that its continued existence was in peril. However, some writers and editors became more provocative, trying to wrestle hard SF back into what they considered the proper shape“ (Cramer, 2003, p. 193).

In this politically and culturally charged environment, cyberpunk emerged with a sharp critique of contemporary science fiction. Writers like William Gibson and Bruce Sterling saw the genre as not only reactionary but overly preoccupied with technological advancements and space exploration, while neglecting the profound technological innovations already transforming everyday life, society, and the individual. In response, they called for a new “radical, hard SF” (Cheap Truth, 1984) that would shift its focus from the stars to the realities of the emerging electronic age. Cyberpunk, therefore, should be understood as the product of a complex interplay of historical, literary, political, and technological forces The explicit goal of cyberpunk was to break away from the tradition of narratives centered on extreme scenarios in space or on distant planets, often featuring protagonists from scientific or military elites (cf. Lem, Heinlein, Clarke, Asimov, and Dick). Instead, cyberpunk refocused attention on Earth and the ways in which high technology was already reshaping daily life. Rather than continuing to modernize the warnings of human hubris through Shelley’s monsters or Asimov’s robots, cyberpunk sought to explore how the rapid fusion of human and machine was already transforming individuals, society, perception, and culture—and how these changes would only intensify in the future.

Gibson and Baudrillard: The Entanglement of Cyberpunk and Media Theory in Shaping Future Imaginaries

Having explored the interplay between Neuralink, the concepts of Interface and Matrix, and their connection to William Gibson, and having traced the breaks in tradition between cyberpunk authors and classical science fiction, the next step is to examine how the concepts and terminology of cyberpunk literature have gained influence far beyond the genre. To understand this, it is necessary to focus on the interweaving of cyberpunk literature with media theory.

This interweaving operates on two interconnected levels. On the one hand, cyberpunk authors like William Gibson drew on media theoretical concepts, incorporating and fictionalizing them in their work. In doing so, these authors often pushed beyond the boundaries of the theories themselves, creatively exploring and sometimes expanding upon their abstract ideas. On the other hand, media theorists and philosophers such as Douglas Kellner, Fredric Jameson, and Rainer Winter engaged with cyberpunk literature, recognizing in these works an artistic realization and continuation of their own theories. These theorists not only analyzed the cyberpunk narratives but also used them as a springboard to further develop their own ideas. The central argument of this paper is that this reciprocal relationship—between cyberpunk fiction and media theory—accounts for the genre’s wide recognition and influence far beyond the boundaries of science fiction. This interplay has left a lasting mark on the intellectual discourse, to the extent that the concepts and terminology introduced by cyberpunk authors continue to shape discussions in various fields today.

As previously discussed, cyberpunk literature is rooted in the desire to break with classical Western notions of an inherent human essence, portraying how technology penetrates deeply into the core of humanity, profoundly and radically transforming it. This reflection, while strongly anchored in the field of science fiction, is not limited to this genre. Rather, it finds its counterpart in academic discourse preceding the rise of cyberpunk literature, a discourse that can be broadly understood today as the project of postmodernism. In discussions of postmodernism, Baudrillard’s ideas were long regarded as the cutting edge of subversive contemporary social theory. In the mid-1970s, Baudrillard began developing his theory of simulation, grounded in the thesis that modern society had undergone a drastic rupture due to the impact of new media technologies. In this context, Baudrillard proclaimed the dissolution of the subject, political economy, meaning, truth, and the social formations of contemporary societies. The representation and analysis of this process, Baudrillard argued, required entirely new theories, concepts, and descriptions. His model of simulation was based on a multiple order of artificial worlds of signs, which he called “simulacra”. Much like McLuhan’s “leading medium”, Baudrillard’s “simulacra” are subject to an evolution throughout history, altering both their form and theoretical significance. According to Baudrillard, the most advanced form of simulacrum is simulation, which has become the dominant feature of modern societies.

For Baudrillard, postmodern society is primarily organized by new mass media technologies, which generate signs, images, and social realities, thus giving rise to a new postmodern culture of simulation. The world of the simulation society, therefore, is governed by codes and models. Baudrillard contends that, from this point onward, humanity exists within a logic of simulation „which no longer has anything to do with a logic of facts and an order of reason. Simulation is characterized by a precession of the model, of all the models based on the merest fact—the models come first, their circulation, orbital like that of the bomb, constitutes the genuine magnetic field of the event“ (Baudrillard, 1981, p.17).

This intersection of cyberpunk and postmodern theory, particularly Baudrillard’s concept of simulation, highlights the way cyberpunk literature not only fictionalizes but also engages deeply with postmodern concerns, specifically the dissolution of stable identities, realities, and truths in an age dominated by technology and media. It is the technologies and media of the postmodern world that shape, modulate, and test mankind. Media take on the role of creating human reality (Baudrillard,1993).Whereas in earlier stages, individuals experienced reality through their visual and sensory perception of the environment, today’s media have developed a life of their own, generating what Baudrillard terms hyperreality: “Simulation is no longer that of a territory, a referential being, or a substance. It is the generation by models of a real without origin or reality: a hyperreal” (Baudrillard, 1981, p.3). The experiences provided to humans through entertainment, information, and communication media are more intense and immersive than the mundane scenes of everyday life. Thus, Baudrillard’s world is one of hyperreality. In this postmodern world, individuals leave the „desert of the real“ (Baudrillard, 1981, p. 38) behind for the ecstasies of hyperreality and the new realms of experience offered by computers, media, and technologies. That these ecstasies are not „real“ is irrelevant, as everything has become a simulation in which it is no longer possible to distinguish between the imaginary and the real.

While Baudrillard’s concept of simulation remains largely abstract, Gibson, in „Neuromancer“, presents a world where simulation and hyperreality are omnipresent through the Matrix. In „Neuromancer“, humans are surrounded by simulations, such as artificial or computer-generated identities and intelligences. Even human individuals can be reconstructed and continue to exist as simulations of themselves. Through the Matrix, a new domain of the hyperreal is envisioned. The Matrix appears more real and complex than anything humans experience in their everyday lives. For example, the protagonist of „Neuromancer“, Case, feels truly alive only within the Matrix—his real life, as he perceives it, takes place there. He disdainfully refers to the body as mere „meat“ (Gibson, 2003, p. 264). Although humans in Gibson’s world can move freely between reality and the virtual reality of the Matrix through the interface, like Baudrillard’s dissolving subject, they often struggle to distinguish between simulation and reality. Baudrillard’s idea of the implosion of reality with other dimensions into a new, multi-dimensional simulation of experiences is thus rendered literarily in Gibson’s work. In some cases, even death may have no significant impact on a person’s physical or virtual existence. During one of Case’s stays in the Matrix, for instance, he is declared brain-dead in the physical world. Meanwhile, the Matrix contains personality constructs based on memories of deceased individuals, and these constructs believe they are the actual individuals.

At the conclusion of „Neuromancer“, the god-like superbeing that emerges from the fusion of two artificial intelligences embodies the totality of the system and possesses its own consciousness. This consciousness is something entirely new: it is neither confined to a body nor limited to hardware but exists independently in the infinite space of the interconnected communication, computer, and satellite networks. The Matrix, in „Neuromancer“, thus acquires a consciousness that both envelops it and transcends it. To echo Elon Musk’s statement, we are dealing here with “the ‘matrix in the matrix’” (Tesmanian, 2020).

However, as we have seen, Musk, after invoking these images, turns away from such visions, advocating for the creation of what he describes as “the good version of cyberpunk worlds.” The technologies being developed by Neuralink, therefore, are intended to ensure the “survival” of humanity by enhancing the human mind and its capabilities to compete with artificial intelligences. Implicitly, Musk is drawing on familiar narratives, images, and ideas, but in the next step, he diverges from them. He explicitly references the anti-humanist cyberpunk vision of the relationship between technology and humanity as a means of addressing the problem.

(Independent.com, 27.07.2020)

As pointed out above, Baudrillard’s ideas were long considered the vanguard of subversive contemporary social theory in the discourse on postmodernism. His thoughts on the radical transformation of modern society found resonance not only in academic circles but also in the artistic avant-garde. Baudrillard’s ideas were frequently adopted, discussed, and contributed to his reputation as a prophet of postmodern theory. A particular focus was placed on Baudrillard’s writing strategies, which fused aesthetics and material from various domains. His texts oscillated between literary and academic styles, gradually dissolving the boundaries between theory and fiction. Despite Baudrillard’s theoretical and discursive subversiveness, critics began to argue as early as the 1980s that his post-1970s work lacked innovation, accusing the French philosopher of reiterating his earlier ideas rather than truly developing them further. Douglas Kellner, associated with the third generation of the Frankfurt School, commented on this critique:

„For some years, Baudrillard was cutting-edge, high-tech social theorist, the most stimulating and provocative contemporary thinker. But in the early 1980s, Baudrillard ceased producing the stunning analyses of the new postmodern scene that won such attention in the previous decade. Burnt out and terminally cynical, Baudrillard has instead churned out a number of mediocre replays of his previous ideas […] Baudrillard’s travelogues, notebooks, theoretical simulations, and occasional pieces fell dramatically below the level of his 1970s work, and it appeared to many that Baudrillard himself had become boring and irrelevant, the ultimate sin for a supposedly avant-garde postmodern theorist“ (Kellner, 1995, p. 298). It was during this very phase that the first works by Gibson and other cyberpunk authors emerged. While Baudrillard „churned out a number of mediocre replays of his previous ideas […] cyberpunk fiction became the literary trend of the moment and for many the avant-garde of theoretical visions and insight“ (Kellner, 1995, p. 298).

This shift in cultural relevance reflects how cyberpunk literature, with its fresh engagement with technology, media, and the human condition, began to occupy the intellectual space once dominated by Baudrillard’s postmodern thought. Due in no small part to this form of positive academic engagement, as demonstrated by Kellner, cyberpunk evolved into a literary trend that crossed disciplinary boundaries, from cultural studies and media theory to gender studies. This development is largely attributable to Douglas Kellner, one of the most prominent figures in cultural studies, whose work has been widely received and influential across multiple academic fields. Kellner himself believed that Gibson’s works offered „powerful visions of a new type of technological society“ where „humans and machines […] constantly imploding and the human itself is dramatically mutating,“ creating „the most impressive bodies of recent writing on the fate of hypertechnological society since Baudrillard’s key texts of the 1970s“ (Kellner, 1995, p. 298). Frederic Jameson also recognized the significant role of cyberpunk literature as early as 1991, remarking that „new writing like cyberpunk determines an orgy of language and representation“ (Jameson, 1991, p. 38).

For Jameson, in particular, Gibson’s innovations were noteworthy: „William Gibson’s representational innovations, indeed, mark his work as an exceptional literary realization within a predominantly visual or aural postmodern production“ (Jameson, 1991, p. 320). Over the years, Jameson has frequently returned to cyberpunk literature, examining works by William Gibson and Bruce Sterling in various contexts, viewing them as the ultimate literary expression rooted in postmodern media theory and philosophy. That Gibson remains relevant for Jameson is evident in one of his more recent works, „The Ancients and the Postmoderns“ (2015), where he dedicates an entire chapter to Gibson’s writing, reading him in conversation with figures like Baudrillard, Debord, Deleuze, and Heidegger. Timothy Leary, meanwhile, attributed to cyberpunk literature a philosophical significance for the postmodern era comparable to that held by the works of Mann, Tolstoy, and Melville for the industrial age (Leary, 1996). Likewise, the American literary scholar Brian McHale, who has explored the mutual influence between postmodern literature, science fiction, and poststructuralist theory, assigned cyberpunk a central position within this framework (McHale, 1992, p. 244). Rainer Winter further advanced this discussion in his 2002 essay, „Die postmodernen Visionen des Cyberpunks“, where he delved deeply into cyberpunk’s visions of the future, its spatial experience of the ‚, and its unique worldview.

Like McLuhan and Baudrillard before them, the authors of cyberpunk literature operated within previously separate domains of philosophy, social sciences, literature, natural sciences, and media culture, attempting to capture the rapid transformations of their present. While Baudrillard has faced criticism (which should be seen less as a critique of his overall work and more as a reflection of the limitations of a theorist within a specific time and context), it is crucial to recognize the foundational role his theoretical groundwork played. Baudrillard’s influence on both academic and non-academic discourse significantly shaped how cyberpunk authors, particularly Gibson, conceptualized and articulated ideas like the Matrix and the interface. Baudrillard’s ideas not only paved the way for these concepts but can be traced, so to speak, into the very DNA of Gibson’s Matrix and interface. Both Baudrillard’s theories of simulation and hyperreality, alongside his concept of the implosion of reality, are closely intertwined with Gibson’s development and expansion of these ideas into the forms of the Matrix and the interface. Through the reception of thinkers like Kellner, Jameson, Winter, and McHale, cyberpunk literature—especially Gibson’s work—has garnered significant academic attention, spreading into a wide range of disciplines. For example, cultural studies have explored the representation of fragmented identity and culture within cyberpunk literature (Cavallaro, 2000; Tatsumi, 2006), gender studies have thoroughly engaged with the hybrid figure of the cyborg and its implications for gender relations (Haraway, 1990; Lavigne, 2012), and even in architecture, scholars have investigated the extrapolated spatial concepts of artificial megacities and their organic building materials as presented in cyberpunk narratives (Wittke, 2006).

This diversity of approaches not only highlights the multifaceted nature of cyberpunk literature but also underscores how the concepts and terms described by cyberpunk authors like Gibson have diffused into broader discourse and various contexts. Gibson’s texts are not only literary reflections on the evolving relationship between humans and machines, alongside the related discourses on the body, reality, and simulation; they also serve as artistic-literary explorations of media and social theories. In this process, Gibson fictionalized the theories he engaged with, popularizing them in the process. Concepts like the Matrix and the interface, drawn from the media theories of figures like McLuhan and Baudrillard, have permeated wider cultural discourse and shaped popular notions of the future.

This dynamic reveals that science, society, and popular culture should not be understood as distinct, autonomous entities. Instead, they must be seen as interdependent dimensions that constantly influence and constitute one another. The case of cyberpunk demonstrates that popular culture, science, discourse, and research are so closely intertwined that they cannot be separated; rather, they shape each other in profound ways. Artistic, scientific, and societal discourses are mutually formative. In the case of Neuralink, the continued influence of the fusion of cyberpunk and media theory is evident. The terms and concepts used to articulate Neuralink’s projects and visions are products of this very interconnection. The contemporary use of these concepts, with clear references to cyberpunk and Gibson by figures like Elon Musk, further illustrates that these ideas have left such a significant imprint on the discourse that they now function as widely recognizable future imaginaries. They evoke images and visions that are familiar to large portions of, at least, Western societies.

The historical trajectory outlined in the article clearly demonstrates that the concepts and ideas developed in Baudrillard’s theory and Gibson’s speculative fiction actively shape public perception and even influence the development of future technologies. Concepts like the Matrix and the interface embody deeply ingrained cultural narratives and imaginations that shape our understanding of technological advancement and the relationship between humans and machines. These concepts contribute to collectively shared societal future imaginaries. The relationship between technological development and societal imaginations is reciprocal. While fiction and theory shape our visions of the future, the technologies we develop, in turn, mold our expectations and the concrete realities of that future. Technology does not emerge in a vacuum; it reflects and reinforces specific societal values, power structures, and imaginations. This dynamic is increasingly recognized by technology firms (the most famous among them might be Sony), as evidenced by the growing popularity of science fiction prototyping and the use of concepts like speculative design and design fiction. The implications of this feedback loop must not only be examined but also brought into societal discourse. The narratives embedded within these designs are crucial, just as cyberpunk is far more than just a genre, and Baudrillard is more than merely a theorist of postmodernism—both continue to shape narratives about how the future may unfold and have thus retained their relevance. The future imaginaries that have emerged from the intersection of Gibson and Baudrillard resonate like echoes, constructing a world in which the boundaries between fiction and reality are increasingly blurred—demonstrating the enduring relevance of Baudrillard’s concepts of hyperreality and simulation even at this level.

References:

Ars Technica. (2017, March 28). Fight AI by becoming AI — Elon Musk is setting up a company that will link brains and computers. Ars Technica. https://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2017/03/elon-musk-is-setting-up-a-company-that-will-link-brains-and-computers/

Atterbery, B. (2003). The magazine era: 1926-1960. In J. Edward & F. Mendelsohn (Eds.), The Cambridge companion to science fiction (pp. 32-55). Cambridge University Press.

Baudrillard, J. (1981). Simulacra and simulation. University of Michigan Press.

Baudrillard, J. (1993). Symbolic exchange and death. Sage Publications.

Benabid, A. L., et al. (2019). An exoskeleton controlled by an epidural wireless brain-machine interface in a tetraplegic patient: A proof-of-concept demonstration. The Lancet Neurology, 18(12), 1119-1127. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30321-7

Cavallaro, D. (2000). Cyberpunk and cyberculture: Science fiction and the work of William Gibson. The Athlone Press.

Cheap Truth. (1984). Cheap truth 5. Retrieved November 8, 2020, from http://www.joelbenford.plus.com/sterling/ct/ct05.txt

Exodus. (2020, November 8). Elon Musk puts his case for a multi-planet civilization. Aeon. https://aeon.co/essays/elon-musk-puts-his-case-for-a-multi-planet-civilisation

Gibson, W. (2003). Burning chrome. HarperCollins.

Gibson, W. (2003). Neuromancer. HarperCollins.

Gözen, J. E. (2012). Cyberpunk science fiction: Literarische Fiktionen und Medientheorie. Transcript Verlag.

Haraway, D. (1990). A manifesto for cyborgs: Science, technology, and socialist feminism in the 1980s. In L. Nicholson (Ed.), Feminism / Postmodernism (pp. 190-233). Routledge.

Harvard Kennedy School. (n.d.). Sociotechnical imaginaries. Science, Technology and Society Research Platform. Retrieved October 19, 2024, from https://sts.hks.harvard.edu/research/platforms/imaginaries/

Hart, R. (2024, February 26). Experts criticize Elon Musk’s Neuralink over transparency after billionaire says first brain implant works. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/roberthart/2024/02/26/experts-criticize-elon-musks-neuralink-over-transparency-after-billionaire-says-first-brain-implant-works/

Hookway, B. (2014). Interface. MIT Press.

Hyperdrive. (2019, February 17). Elon Musk left OpenAI to focus on Tesla, SpaceX. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-02-17/elon-musk-left-openai-on-disagreements-about-company-pathway

James, P. (2019). The social imaginary in theory and practice. In C. Hudson & E. K. Wilson (Eds.), Revisiting the global imaginary (pp. 33-47). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-14911-6_3

Jameson, F. (1991). Postmodernism, or, the cultural logic of late capitalism. Duke University Press.

Jasanoff, S., & Kim, S. (2015). Dreamscapes of modernity: Sociotechnical imaginaries and the fabrication of power. University of Chicago Press.

Jewett, C. (2024, May 22). Despite setback, Neuralink’s first brain-implant patient stays upbeat. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/22/health/elon-musk-brain-implant-arbaugh.html

Kellner, D. (1995). Media culture: Cultural studies, identity and politics between the modern and the postmodern. Routledge.

Kleske, J. (n.d.). Future imaginaries definition. Retrieved October 19, 2024, from https://johanneskleske.com/future-imaginaries-definition/

LA Times. (2017, April 21). A quick guide to Elon Musk’s new brain-implant company, Neuralink. LA Times. https://www.latimes.com/business/technology/la-fi-tn-elon-musk-neuralink-20170421-htmlstory.html

Lavigne, C. (2012). Cyberpunk women, feminism and science fiction. McFarland.

Leary, T. (1996). Quark of the decade. Mondo 2000, 7, 53-56.

McHale, B. (1992). Constructing postmodernism. Routledge.

Metz, C. (2019, July 16). Elon Musk’s Neuralink wants ‘sewing machine-like’ robots to wire brains to the Internet. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/16/technology/neuralink-elon-musk.html

Moran, M. (2019, July 18). Elon Musk looks to wire your brain to the Internet. The Irish Times. https://www.irishtimes.com/business/innovation/elon-musk-looks-to-wire-your-brain-to-the-internet-1.3959033

Neuralink. (2020). Interfacing with the brain. Neuralink. https://neuralink.com/approach/

Nicolas-Alonso, L. F., & Gomez-Gil, J. (2017). Brain computer interfaces, a review. Sensors, 12(2), 1211-1279. https://hal.inria.fr/hal-01656743/document

Robotic Biz. (2020, November 8). Neuralink – A step closer to human-machine symbiosis. Robotic Biz. https://roboticsbiz.com/neuralink-a-step-closer-to-human-machine-symbiosis

Science Media Center. (2020). Brain-machine interfaces – Gehirn und Maschine verknüpft. Science Media Center. https://www.sciencemediacenter.de/alle-angebote/fact-sheet/details/news/brain-machine-interfaces-gehirn-und-maschine-verknuepft

SiddharthVlogs. (2020, November 8). Is Elon Musk creating the Matrix? | Neuralink explained [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z9Ts0NFkMco&ab_channel=SiddharthVlogs

Sterling, B. (1988). Mirrorshades: The cyberpunk anthology. HarperCollins.

Sterling, B. (1991). Cyberpunk in the nineties. Retrieved November 8, 2020, from www.streettech.com/bcp/BCPtext/Manifestos/CPInThe90s.html

Tatsumi, T. (2006). Full metal apache: Transactions between cyberpunk Japan and avant-pop America. Duke University Press.

Technology Review. (2017, April 25). Mind-reading robots: CSAIL system lets humans correct robots’ mistakes by thinking. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2017/04/25/152264/mind-reading-robots/

Technology Review. (2020, August 30). Elon Musk’s Neuralink is neuroscience theater. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2020/08/30/1007786/elon-musks-neuralink-demo-update-neuroscience-theater/

Tesmanian. (2020, August 28). Neuralink will show ‘The Matrix in the Matrix’ on August 28, says Elon Musk. Tesmanian. https://www.tesmanian.com/blogs/tesmanian-blog/neuralink-matrix

William Gibson: The man who saw tomorrow. (2014, July 28). The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/jul/28/william-gibson-neuromancer-cyberpunk-books

Winter, R. (2002). Die postmodernen Visionen des Cyberpunks. Zeitschrift für Medienwissenschaft, 3, 45-67.

Wittke, K. (2006). Architekturphantasien im Science-Fiction-Roman Schismatrix von Bruce Sterling. In A. Geiger & S. Hennecke (Eds.), Imaginäre Architekturen: Raum und Stadt als Vorstellung (pp. 190-201). Parerga Verlag.

Discover more from BAUDRILLARD NOW

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.